LONDON AFTER MIDNIGHT

(USA, 1927)

December 17th, 1927, was the American premiere of an unusual Christmas movie. Starring Lon Chaney and directed by regular collaborator Tod Browning, this proved to be their biggest hit at the box office.

But after the initial cinema release, this silent movie was rarely (if ever?) revived and by the time Chaney's work became better appreciated and started being restored, all existing prints of London after Midnight had been lost. The last known copy was destroyed in a studio vault fire. Not even a fragment or a trailer has been found. There are regular rumours and hoaxes announcing that it's been found (one just last week) that keep raising our collective hopes.

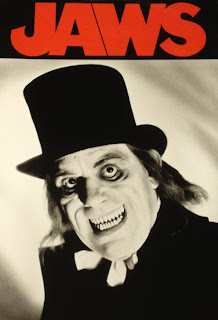

London After Midnight is now one of the most sought after lost films, demand fuelled by the tremendous publicity photos of Chaney's fearsome character, 'The Man in the Beaver Hat', one of the earliest depictions of a vampire in American cinema. With these photos we can still appreciate his effective, unique, painful make-up, but what we've lost is any movement from this superb, physical performer. A bent-legged hunchbacked figure, creeping towards the camera down a long corridor, descending triumphantly down a cobwebbed staircase, his grinning face in close-up as he hypnotises his victims...

But we can still experience London After Midnight in other ways, and better understand what's been lost. While The Man in the Beaver Hat is now a horror movie icon, this film is from the silent Hollywood genre of mystery movies, when haunted houses and supernatural subjects always had Scooby-Doo explanations...

David Skal and Elias Savada, authors of Dark Carnival: The Secret World of Tod Browning, conclude that Browning's story was inspired Dracula, a huge stage hit at the time. The mansion next to a decaying ruin is the central plot of Dracula boiled down to two locations - the vampire's lair and a nearby house full of prey. London includes an empty coffin, bats, howling dogs, neck bites, a vampire who transforms into mist, targeting a young woman while her suitor and a vampire expert are powerless to protect her. There's the suggestion that Browning wrote this when he couldn't get the rights to film Dracula (but he got that chance four years later).

The scriptbook and photo-reconstruction

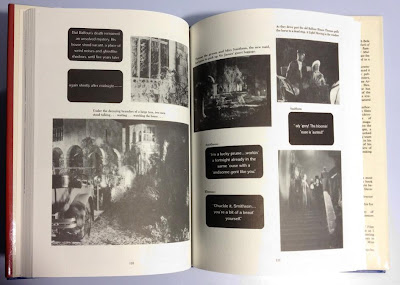

Browning's original story 'The Hypnotist' was rewritten as a script by Waldemar Young (The Unholy Three, The Unknown, Island of Lost Souls). If you find it easy to read scripts, the second draft was published in 1985 in this book by Philip J Riley. Dated July 1927, the script describes only what was envisioned. Several key scenes were later omitted, other scenes shot but left out.

The book includes a reminiscence from Forrest Ackerman (who saw London After Midnight when it first opened), original publicity material, shots of the sets, and even Lon's special 'location' make-up box just used for this film.

Even back in 1985, there was a longing to to reclaim this film, Riley's astonishing research providing this superbly detailed book. My first chance to experience London After Midnight. And also quite a deflation of my expectations. Not the film you'd expect from the photos of Chaney's vampire. I was hoping for another Dracula.

Once an expensive hardback edition, this wonderful book is still available in paperback reprints and even available for Kindle.

The novelisation

As a script, the story is quite confusing, though the photo reconstruction demonstrates that the finished version simplified the set-up, adding as many red herrings as possible. But the novel proved immensely helpful in understanding the plot, defining the characters and their motivations. It's not really a novel, but an adaption of the original script and was first published in the UK and US in 1928.

While recent novelisations have a reputation for being swiftly written and even wildly inaccurate, Marie Coolidge-Rask produced an atmospheric, well-written tale with less comedy, more romance and drama. However, she's so thorough, that the mystery is far too easy to solve from the start, allowing room for only one real suspect! The elaborate scheme is detailed enough to make all the subsequent versions easier to follow. The first several chapters set up the story before the events of the film kick in.

|

| The 1928 novelisation includes photos from the film |

While I bought this tattered original 1928 copy off eBay several years ago, this early example of a movie tie-in has recently been reprinted, with its original photo inserts, in this paperback edition and also this brand new limited edition.

My copy of the novelisation is bare, though I've just found that this site sells replica dust covers!

The TCM recreation

In 2003, Turner Classic Movies attempted their own resurrection of London After Midnight for a special Halloween programme, later released on this Lon Chaney DVD set.

An unprecedented attempt to rebuild an entire movie from its publicity photographs was initially disappointing. Partly because of the amount of talky melodrama. There are many creepy scenes in the film, but these pass by too quickly. I'm sure many films from this era would also have an uninspiring effect, given the same presentation.

But for me, there's still room for improvement. The photos have been filmed overusing movements that wouldn't have been in the film. The rostrum camera swoops across the photos in ways the camera wouldn't have. It would have been static shots - wide, medium and close - with most camera moves only tracking as a wide shot. More importantly, the editing style often fails to identify which character is speaking the lines shown in the intertitles, making it harder to follow.

The advantage this has over Riley's photo-reconstruction in print, is that the photos are better reproduced and often shown in closer detail. Reading the novel, studying the script and watching the reconstruction all helped me follow the story better, with a fuller idea of the horrific Chaney scenes that we've lost. But I'm still no closer to knowing how he might have moved, or the effect on screen.

This 2-disc set also includes a superb feature-length documentary about Chaney's life, including surviving clips from others of his lost films.

The remake - MARK OF THE VAMPIRE (1935)

Further help is at hand. Eight years later, London After Midnight was remade, with sound, by the same director. But by the time Tod Browning shot Mark of the Vampire, he'd made Dracula with Bela Lugosi, and Chaney had tragically died. Only logical that Lugosi should step in to play the vampire in this remake. But without the beaver fur hat or use of any distorting make-up.

A different approach in many ways, the remake provides further clues as to how London looked. Remakes with sound often copied the most effective scenes from the silent originals, even recycling hard-to-film footage (sadly not the case here). While the story has been tweaked further, the setting isn't even London this time, Browning appears to be jibing the audience by repeating elements from his Dracula, the early scene in the superstitious middle-European village, the variety of weird animals scurrying around the ruined mansion, even Lugosi walking through a cobweb. There are just as many references to Dracula as London After Midnight.

Lon Chaney's original character of the investigator is now split between two major actors, Lionel Atwill and Lionel Barrymore. Atwill (Son of Frankenstein, Mystery of the Wax Museum, Doctor X, Murders in the Zoo) provides a determined and believable police inspector, already a great horror actor for helping the surreal seem real. But the top-billed Lionel Barrymore treats this more like pantomime, overplaying every line, patronisingly preaching vampire lore, at the same time softening it with a self-amused smile as if tipping off audience that it's just hokum. He dominates the film and sets a light tone - perhaps the studio wanted less of a horror film and were pulling back from the harshness of the 'suicide'. The bleeding hole in Lugosi's temple constantly reminds us that the mystery centres on Lord Balfour shooting himself in the head.

Admittedly Barrymore was one of the few actors who could attempt to replace Lon Chaney. But I liked him far more in The Devil Doll (1936), again for director Browning, in a dual role that echoes Lon Chaney's two versions of The Unholy Three.

Mark of the Vampire is a good introduction to the characters, story and structure of London After Midnight, right down to the mix of scares and comedy.

It also gives us an idea of the special effects that might have been used - the way the vampire emerges from the mist, and the flight of the 'bat girl'. Note that despite being a single shot, the trailer for Mark of the Vampire uses a completely different take to the more spectacular one in the film. Hopefully absent from London After Midnight is the large, slow-moving model bat that hovers more than it flies. It might even have been intentionally playing for laughs, Lugosi patiently waiting for it to pass by.

It also gives us an idea of the special effects that might have been used - the way the vampire emerges from the mist, and the flight of the 'bat girl'. Note that despite being a single shot, the trailer for Mark of the Vampire uses a completely different take to the more spectacular one in the film. Hopefully absent from London After Midnight is the large, slow-moving model bat that hovers more than it flies. It might even have been intentionally playing for laughs, Lugosi patiently waiting for it to pass by.

A possible echo of Chaney's crouched walk is glimpsed when Lugosi also goes into a low stalk directly towards the camera down a similar corridor. Though it cuts off remarkably early for something that could have been quite horrifying. Lugosi's face is even distorted into an animal snarl.

Mark of the Vampire is available in a great MGM boxset of early horror films, on a double-bill DVD with the pre-code delight, The Mask of Fu Manchu.

In conclusion, I'd suggest that anyone new to London After Midnight starts by watching Mark of the Vampire, to introduce themselves to the story, the characters and the plot twists as effectively as possible. Then try one of the photo-reconstructions, either the TCM recreation or the Riley scriptbook, to compare the differences from the remake. Then read the novel to expand on the original story and characters, and catch up on the scenes that were even cut from the original film, including an extra murder!

In conclusion, I'd suggest that anyone new to London After Midnight starts by watching Mark of the Vampire, to introduce themselves to the story, the characters and the plot twists as effectively as possible. Then try one of the photo-reconstructions, either the TCM recreation or the Riley scriptbook, to compare the differences from the remake. Then read the novel to expand on the original story and characters, and catch up on the scenes that were even cut from the original film, including an extra murder!

To find out more about the amazing life and work of Lon Chaney, Michael F. Blake has published several books based on his superb researches.